DID YOU KNOW.

MCL 722.27(1)(c) provides that in a custody dispute, a trial court, for the best interests of the child at the center of the dispute, may “modify or amend its previous judgments or orders for proper cause shown or because of change of circumstances.”

[Principle source e-journal #71713, Unpublished 11/14/19.No.349021. ]

But the court is not permitted to “modify or amend its previous judgments or orders or issue a new order so as to change the established custodial environment of a child unless there is presented clear and convincing evidence that it is in the best interest of the child.” MCL 722.27(1)(c).

“These initial steps to changing custody— finding a change of circumstance or proper cause and not changing an established custodial environment without clear and convincing evidence—are intended to erect a barrier against removal of a child from an established custodial environment and to minimize unwarranted and disruptive changes of custody orders.” Vodvarka v Grasmeyer, 259 Mich App 499, 509; 675 NW2d 847 (2003) (quotation marks omitted).

The first step in the analysis is to determine whether the moving party has established proper cause or a change of circumstances by a preponderance of the evidence. Id. at 508-509.

In McRoberts v Ferguson, 322 Mich App 125, 131-132; 910 NW2d 721 (2017), this Court explained: Proper cause means one or more appropriate grounds that have or could have a significant effect on the child’s life to the extent that a reevaluation of the child’s custodial situation should be undertaken.

In order to establish a change of circumstances, a movant must prove that, since the entry of the last custody order, the conditions surrounding custody of the child, which have or could have a significant effect on the child’s well-being, have materially changed.

To constitute a change of circumstances under MCL 722.27(1)(c), the evidence must demonstrate something more than the normal life changes (both good and bad) that occur during the life of a child, and there must be at least some evidence that the material changes have had or will almost certainly have an effect on the child. [Citations, quotation marks, and alterations omitted.]

With respect to the issue of “proper cause,” the criteria outlined in the statutory best

interest factors, MCL 722.23, “should be relied on by a trial court in deciding if a particular fact raised by a party is a ‘proper’ or ‘appropriate’ ground to revisit custody orders.” Vodvarka, 259 Mich App at 512.

In regard to “change of circumstances,” the relevance of facts presented should also “be[] gauged by the statutory best interest factors.” Id. at 514. “Although the threshold consideration of whether there was proper cause or a change of circumstances might be fact-intensive, the court need not necessarily conduct an evidentiary hearing on the topic.” Corporan, 282 Mich App at 605.

In Vodvarka, 259 Mich App at 512, this Court, addressing the threshold issue, observed: Obviously, trial courts must make this factual determination case by case. Although these decisions will be based on the facts particular to each case, we do not suggest that an evidentiary hearing is necessary to resolve this initial question.

Often times, the facts alleged to constitute proper cause or a change of circumstances will be undisputed, or the court can accept as true the facts allegedly comprising proper cause or a change of circumstances, and then decide if they are legally sufficient to satisfy the standard.

MCR 3.210(C)(8) provides: In deciding whether an evidentiary hearing is necessary with regard to a postjudgment motion to change custody, the court must determine, by requiring an offer of proof or otherwise, whether there are contested factual issues that must be resolved in order for the court to make an informed decision on the motion.

It is clear to us, and was effectively accepted by the trial court, that if the allegations set forth in plaintiff’s motion to modify custody are true, they would easily establish a change of circumstances and proper cause for purposes of revisiting the issue of custody under the statutory best-interest factors.

But the trial court found it problematic that plaintiff had not submitted any statements, affidavits, reports, or other documentary evidence to support the allegations, let alone evidence that was current and relevant.

The motion to modify custody was not verified, nor did plaintiff supply her own affidavit. MCR 3.210(C)(8) allowed the trial court to require “an offer of proof or otherwise” in relation to deciding whether to order an evidentiary hearing.

Under the circumstances of the case and given the remarks made by the trial court when ruling on the motion, the court’s hesitation and resistance at giving any weight to the allegations in plaintiff’s motion was plainly driven by the four CPS investigations instigated by plaintiff that resulted in determinations that allegations of abuse by defendant could not be substantiated.

The lack of substantiation, again and again, could reasonably call into question plaintiff’s motives and credibility on all matters.

The trial court appeared more than open to further considering a motion to modify custody if plaintiff would come forward with supporting documentary evidence, explaining why the court took the unusual step of denying the motion without prejudice.

Indeed, the record and the CPS history support the trial court’s decision to deny the motion to modify custody simply on the-1970 basis that plaintiff did not provide supporting documentation on the threshold issue of change of circumstances or proper cause."

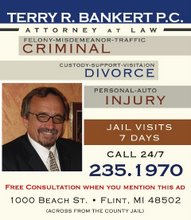

Presented here by Terry Bankert Flint Divorce Attorney 810-235-1970 FlintFamilyLaw.com