A LITTLE ABOUT PPO’S

6/10/2008 Hot off the press’s

[note this case was modified for media presentation, do not rely on it without reviewing the original and seeking advice of counsel.-trb]

Issues:

Michigan Court of Appeals published opinion.

Whether the trial court properly granted and continued a PPO against respondent-Mark Hayford (petitioner-Dirk Hayford's father); Standard of review; Pickering v. Pickering; MCL 600.2950(4); Kampf v. Kampf;

Whether the PPO impermissibly modified respondent's custody of his son (petitioner);

Whether the Child Custody Act is the exclusive means through which custody of the son may be modified; MCL 552.605b; MCL 722.22(d); MCL 722.27(1)(c); Bowie v. Arder; Bert v. Bert;

Whether a PPO must always comply with the Child Custody Act (CCA); Brandt v. Brandt; "Catchall provision" in MCL 600.2950(1)(j); Woodard v. Custer;

Whether there were sufficient acts of harassment or stalking to support the PPO (MCL 600.2950(1)(i)); MCL 750.411h(1)(c), (d), and (e);

Whether the petitioner was required to be afraid or show fear; "Emotional distress" (MCL 750.411h(1)(b)); Sweebe v. Sweebe;

Whether respondent's conduct was constitutionally protected; Nastal v. Henderson & Assocs. Investigations, Inc.;

Rebuttable presumption the victim felt "terrorized, frightened, intimidated, threatened, harassed, or molested" by respondent's conduct (MCL 750.411h(4))

Court: Michigan Court of Appeals (Published)

Case Name: Hayford v Hayford

e-Journal Number: 39600

http://www.michbar.org/opinions/appeals/2008/061008/39600.pdf

Judge(s): Per Curiam - Whitbeck, O'Connell, and Kelly

DIRK HAYFORD,

Petitioner-Appellee,

FOR PUBLICATION

June 10, 2008

9:00 a.m.

v No. 276176

Cass Circuit Court

MARK HAYFORD,

LC No. 06-000924-PP

Respondent-Appellant.

Before: Whitbeck, P.J., and O’Connell and Kelly, JJ.

PER CURIAM.

HAPPY FATHERS DAY , SON GETS PPO AGAINST FATHER

The court held the trial court's decision to grant and continue a PPO against respondent at the request of petitioner, his son who was 18 years of age at the time, fell within the range of principled outcomes.

SON GOT SICK

In November 2006, petitioner, a high school senior, was diagnosed with a potentially cancerous tumor requiring surgery.

DAD ON THE HOOK FOR MEDICAL COSTS

Petitioner's parents were divorced and respondent was contacted for insurance purposes. The divorce judgment stipulated respondent was required to support petitioner and provide medical care until he graduated from high school. Petitioner turned 18 years of age on December 5, 2006.

DAD HANDLES FIRE ARMS FOR A LIVING

Prior to the issuance of the PPO, respondent earned a living building rifles and firearms. Because a PPO is considered a domestic violence offense, respondent may permanently lose his license and livelihood.

DAD SAYS PPO’S MODIFIED CUSTODY ORDER....CREATIVE ARGUMENT..WRONG!

He maintained the PPO should not have been issued and sought a nunc pro tunc order declaring it invalid. Although respondent argued the PPO impermissibly modified custody of his son and the CCA was the exclusive means through which custody could be modified, the court disagreed.

THE KID IS AN ADULT

Since petitioner had reached majority age before seeking the PPO, the CCA was inapplicable. Further, the court recognized in Brandt a PPO need not comply with the CCA under certain circumstances.

DAD LEAVE ME ALONE SAYS KID

The petitioner made it clear to respondent he did not wish further contact. However, respondent's conduct demonstrated his inability to honor his son's wishes. He continued to place telephone calls to petitioner's cell phone and residence, attended a band concert at petitioner's school, placed an ad in the newspaper with petitioner's name and the names of family members and other personal information, prompting questions about the ad, contacted petitioner's physician's office many times causing the doctor to be wary of treating him, and visited the hospital before petitioner's surgery causing him stress before the operation.

PPO PROTECTS THE CHILD FROM THE FATHER

At most, the PPO merely temporarily modified respondent's custody rights in order to prevent further harassment as petitioner dealt with his difficult medical condition. Further, the trial court properly held petitioner experienced emotional distress based on respondent's conduct. Affirmed.

THE COURTS DECISION

Respondent appeals as of right the trial court’s decision to grant and continue a personal

protection order (PPO) against him at the request of petitioner, his son, who was 18 years of age

at the time. We affirm.

A LITTLE MORE DETAIL

In November 2006, petitioner, a high school senior, was diagnosed with a potentially

cancerous tumor that required surgery. Respondent was contacted for insurance purposes.

Petitioner’s parents were divorced and the order or judgment stipulated that respondent was

required to support petitioner and provide medical care until he graduated from high school.

Petitioner turned 18 years of age on December 5, 2006.

PPO EXPIRED ...REPUTATION DAMAGED FOREVER

Although the PPO has been terminated since the filing of this appeal, this appeal is not

moot. Before the PPO was issued, respondent earned a living building rifles and other firearms.

Because a PPO is considered a domestic violence offense, respondent may permanently stand to

lose his license and livelihood. Respondent maintains the PPO should never have issued and

seeks a nunc pro tunc order declaring it invalid.

WHAT IS THE STANDARD WHEN A HIGHER COURT REVIEWS THE DECISION OF A LOWER COURT...ABUSE OF DISCRETION

We review a trial court’s determination whether to issue a PPO for an abuse of discretion

because it is an injunctive order. Pickering v Pickering, 253 Mich App 694, 700-701; 659

NW2d 649 (2002); MCL 600.2950(30)(c). "An abuse of discretion occurs when the decision

resulted in an outcome falling outside the principled range of outcomes." Woodard v Custer,

476 Mich 545, 557; 719 NW2d 842 (2006). A trial court’s findings of fact are reviewed for clear

error. Sweebe v Sweebe, 474 Mich 151, 154; 712 NW2d 708 (2006). We review de novo

questions of statutory interpretation. State Farm Fire & Casualty Co v Corby Energy Services,

Inc, 271 Mich App 480, 483; 722 NW2d 906 (2006).

RULE ABOUT PPO’S

The trial court must issue a PPO under MCL 600.2950(4) if it finds that "there is

reasonable cause to believe that the individual to be restrained or enjoined may commit 1 or

more of the acts listed in subsection (1)." The relevant acts include:

(a) Entering onto premises.

* * *

(g) Interfering with petitioner at petitioner’s place of employment or education

or engaging in conduct that impairs petitioner's employment or educational

relationship or environment.

* * *

(i) Engaging in conduct that is prohibited under section 411h or 411i of the

Michigan penal code, 1931 PA 328, MCL 750.411h and 750.411i.

(j) Any other specific act or conduct that imposes upon or interferes with

personal liberty or that causes a reasonable apprehension of violence. [MCL

600.2950(1).]

Petitioner bears the burden of establishing reasonable cause for issuance of a PPO, Kampf v

Kampf, 237 Mich App 377, 385-386; 603 NW2d 295 (1999), and of establishing a justification

for the continuance of a PPO at a hearing on respondent’s motion to terminate the PPO,

Pickering, supra at 699; MCR 3.310(B)(5). The trial court is required to consider testimony,

documents, and other proffered evidence, and whether respondent previously engaged in the

listed behaviors. MCL 600.2950(4).

Respondent argues that the PPO impermissibly modified custody of his son and that the

Child Custody Act is the exclusive means through which custody of his son may be modified.

We disagree.

Because petitioner reached majority age before seeking the PPO, the Child Custody Act

was inapplicable with respect to custody issues, although still applicable regarding child support.

The Child Custody Act defines a "child" as "minor child and children. Subject to section 5b of

the support and parenting time enforcement act, 1982 PA 295, MCL 552.605b, for purposes of

providing support, child includes a child and children who have reached 18 years of age." MCL

722.22(d). MCL 552.605b permits a child support order for a child who is 18 years of age, or if

he is still in high school, until the child reaches 19 years and 6 months of age. "Child" otherwise

means a minor under the act. While the Child Custody Act and the support and parenting time

enforcement act may provide an age extension for purposes of child support for a child who has

reached majority age but has not graduated from high school, no extension exists for custody and

visitation orders for a child who has reached majority age but is still in high school. Generally,

once the circuit court exercises jurisdiction over a child and issues an order under the Child

Custody Act, "the court’s jurisdiction continues until the child is eighteen years old, MCL

722.27(1)(c)." Bowie v Arder, 441 Mich 23, 53; 490 NW2d 568 (1992). As this Court explained

in Bert v Bert, 154 Mich App 208, 211; 397 NW2d 270 (1986), "jurisdiction in divorce cases is

purely statutory and every power exercised by the circuit court must have its source in a statute

or it does not exist. . . . The divorce court’s jurisdiction over child custody and visitation matters

continues until the parties’ children reach age eighteen."

Further, this Court has recognized that a PPO need not comply with the Child Custody

Act under certain circumstances. In Brandt v Brandt, 250 Mich App 68, 69; 645 NW2d 327

(2002), this Court upheld the trial court’s issuance of a PPO prohibiting the respondent from

contacting his children without first holding a hearing to assess the "best interests of the child"

under the Child Custody Act. The trial court was not making a custody determination when it

issued a PPO, but "was simply issuing an emergency order, which was essentially an award of

temporary custody of the children to petitioner, while granting respondent parenting time until

the divorce proceeding was initiated so that the children might be protected from physical

violence or emotional violence or both inflicted on them by respondent." Id. at 70. This Court

further determined that the trial court in Brandt had authority under the PPO "catchall"

provision, MCL 600.2950(1)(j), to issue the PPO and prohibit contact. Id.

In the instant case, petitioner made it clear to respondent that he did not wish further

contact. However, respondent’s behavior demonstrated his inability to honor those wishes. He

continued to place telephone calls to petitioner’s cellular telephone and residence. Respondent

attended a band concert at petitioner’s school. He placed an advertisement in the newspaper with

petitioner’s name, the names of his family members, and other personal information, prompting

coworkers of both petitioner and his mother to question them about the advertisement.

Respondent contacted petitioner’s physician’s office sufficient times to cause the doctor to be

wary of treating petitioner, and respondent visited the hospital on the day of petitioner’s surgery,

causing him stress immediately beforehand. At most, the PPO merely temporarily modified

respondent’s custody rights in order to prevent continued harassment of petitioner and his family

by respondent as petitioner dealt with his difficult medical condition. Moreover, contrary to

respondent’s assertion, the trial court did not prohibit, as part of the PPO, the exchange of

medical information, or modify the custody order. Accordingly, the trial court’s decision to

issue and continue a PPO against respondent fell within the range of principled outcomes.

Woodard, supra.

Respondent additionally argues there were insufficient acts of harassment or stalking on

record to support the PPO. MCL 600.2950(1)(i) prohibits stalking, defined in MCL 750.411h as

"a willful course of conduct involving repeated or continuing harassment of another individual

that would cause a reasonable person to feel terrorized, frightened, intimidated, threatened,

harassed, or molested and that actually causes the victim to feel terrorized, frightened,

intimidated, threatened, harassed, or molested." MCL 750.411h(1)(d).

"Harassment" is defined in MCL 750.411h(1)(c):

conduct directed toward a victim that includes, but is not limited to, repeated or

continuing unconsented contact that would cause a reasonable individual to suffer

emotional distress and that actually causes the victim to suffer emotional distress.

Harassment does not include constitutionally protected activity or conduct that

serves a legitimate purpose.

"Unconsented contact" is defined as:

any contact with another individual that is initiated or continued without that

individual's consent or in disregard of that individual's expressed desire that the

contact be avoided or discontinued. Unconsented contact includes, but is not

limited to, any of the following:

(i) Following or appearing within the sight of that individual.

(ii) Approaching or confronting that individual in a public place or on private

property.

(iii) Appearing at that individual's workplace or residence.

(iv) Entering onto or remaining on property owned, leased, or occupied by

that individual.

(v) Contacting that individual by telephone.

(vi) Sending mail or electronic communications to that individual.

(vii) Placing an object on, or delivering an object to, property owned, leased,

or occupied by that individual. [MCL 750.411h(1)(e).]

There must be evidence of two or more acts of unconsented contact that caused emotional

distress and would cause a reasonable person emotional distress. MCL 750.411h(1)(a).

Against petitioner’s wishes and despite the fact that he was facing a difficult health

ordeal, respondent appeared at his high school, at the hospital, repeatedly attempted contact via

his cellular and home telephones, contacted petitioner’s treating physician at least three times,

and placed an advertisement in the newspapers containing personal information. Further,

respondent also told petitioner that, "I’ll be everywhere you go and in your back pocket." Based

on the record, there were sufficient acts of harassment to justify the issuance of a PPO, and the

trial court’s finding that respondent’s behavior was harassing and emotionally abusive was not

clearly erroneous.

We also find the trial court’s findings regarding the events at the hospital and the letter

sent to petitioner’s oral surgeon sufficiently supported by the record. The trial court’s findings

regarding the events at the hospital on the day of petitioner’s surgery were based on respondent’s

own testimony that he went to the hospital in an attempt to give his son and his doctor the

medical history information. As for the letter, the trial court’s ruling did not specifically find that

respondent had composed the letter, but did attribute the letter and its tone to respondent.

Although respondent testified that his wife sent the letter, he also testified as to the contents of

the letter without indicating any disagreement with its tone or content. Respondent failed to

object or correct the trial court when it asked him questions referring to respondent as the letter’s

author: "So this is a letter that you wrote to the dentist?"; "Why didn’t you say Dirk’s mother?";

"You’re writing this to the dentist?"; and "And so at this point in time you’re writing this kind of

letter rather than saying, ‘I am Dirk’s father. I’m responsible for health—his health insurance."

Based on the testimony, it was not erroneous to conclude that respondent, at the minimum, knew

and approved of the letter’s contents and tone.

We further conclude that the trial court did not err in holding that petitioner experienced

emotional distress as set forth in the stalking statute, MCL 750.411h, and that the statute did not

require a showing of fear. Respondent offers no support for his assertions that the level of

emotional distress required under MCL 750.411h is a "heightened" standard, or that the distress

must manifest itself as fear. The relevant portion of the statute does not require that the

petitioner feel afraid or make any mention of fear. MCL 750.411h(1)(b) defines "emotional

-5-

distress" as "significant mental suffering or distress that may, but does not necessarily, require

medical or other professional treatment or counseling." The harassment must cause the

petitioner to feel emotional distress and would cause a reasonable person to feel emotional

distress, but it does not specify that this distress must present itself as fear. MCL 750.411h(1)(c).

Presumably, emotional distress can manifest in more forms that fear. Furthermore, the statute

lists several emotional reactions that the petitioner may have in response to stalking: terrorized,

frightened, intimidated, threatened, harassed, or molested. MCL 750.411h(1)(d). While many of

them do in fact involve fear, the inclusion of "harassed" and "molested" demonstrate that fear is

not necessarily required.

Petitioner explained that respondent’s behavior caused him to feel stressed, embarrassed,

and harassed. Respondent’s actions penetrated petitioner’s school, work, and family life, and

affected other members of his family, which caused further distress as a result. Petitioner and his

family had to resort to such lengths as changing their home telephone number in order to avoid

contact with respondent. Considering all the evidence presented at the hearing, the trial court

correctly concluded that petitioner did in fact experience, and a reasonable person would also

have experienced, significant mental stress as a result of respondent’s conduct. In sum, the trial

court’s findings of fact were not clearly erroneous, and this Court is not convinced that a

different conclusion should have been reached. Sweebe, supra.

Respondent next argues that his conduct is protected because it served a legitimate

purpose. Conduct that is constitutionally protected or that serves a legitimate purpose does not

constitute "unconsented contact" and thus cannot amount to harassment. Nastal v Henderson &

Assocs Investigations, Inc, 471 Mich 712, 723; 691 NW2d 1 (2005); MCL 750.411h(1)(c). The

Michigan Supreme Court has interpreted the phrase "conduct that serves a legitimate purpose" to

mean "conduct that contributes to a valid purpose that would otherwise be within the law

irrespective of the criminal stalking statute." Nastal, supra at 723.

Respondent’s chosen method for obtaining medical information about petitioner–posting

an advertisement in the newspaper–was not necessarily to "serve" a legitimate purpose. It was a

highly unusual and extraordinary method for obtaining the information, especially by a father

who was aware that his 18-year-old son was facing a frightening medical condition. Further,

MCL 750.411h(4) provides that a rebuttable presumption arises that the victim is caused to feel

"terrorized, frightened, intimidated, threatened, harassed, or molested" if a person continues to

engage in unconsented contact even after the victim asks him to discontinue this behavior or any

further unconsented contact. Here, there was evidence that petitioner asked respondent to stop

calling or contacting him and to refrain from attending his school function and the operation at

the hospital; nonetheless respondent continued to engage in these behaviors. Even if respondent

had a partially legitimate motive for the contact, the trial court was entitled to conclude that

respondent was not acting for a legitimate purpose based on the evidence.

Affirmed.

/s/ William C. Whitbeck

/s/ Peter D. O’Connell

/s/ Kirsten

[note this case was modified for media presentation, do not rely on it without reviewing the original and seeking advice of counsel.-trb]

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Monday, June 09, 2008

With joint custody can you move 400 miles?

In a recent Michigan Court of Appeals (Unpublished) Case Name: Perreault v. Sullivan The court found that after mom moved , 400 milers away, her improved housing did not have the capacity to benefit the parties' child and her motion to change domicile was denied. The court found that dads parenting time was disrupted by the move. The parties had joint legal custody and mom needed the courts permission to move.

A parent with joint legal custody who seeks to relocate more than 100 miles away must

establish by a preponderance of the evidence that a change in the minor’s domicile is warranted.

In considering a proposed change of a child’s domicile after a divorce, a

court must consider the D’Onofrio1 factors, which are codified at MCL 722.31(4), and provide

that a court must address the following:

(a) Whether the legal residence change has the capacity to improve the

quality of life for both the child and the relocating parent.

(b) The degree to which each parent has complied with, and utilized

his or her time under, a court order governing parenting time with the child, and

whether the parent’s plan to change the child’s legal residence is inspired by that

parent’s desire to defeat or frustrate the parenting time schedule.

©) The degree to which the court is satisfied that, if the court permits

the legal residence change, it is possible to order a modification of the parenting

time schedule and other arrangements governing the child’s schedule in a manner

that can provide an adequate basis for preserving and fostering the parental

relationship between the child and each parent; and whether each parent is likely

to comply with the modification.

(d) The extent to which the parent opposing the legal residence change

is motivated by a desire to secure a financial advantage with respect to a support

obligation.

(e) Domestic violence, regardless of whether the violence was directed

against or witnessed by the child.

After reviewing the record in this case, we find that the circuit court considered each

factor mandated by MCL 722.31(4).

The parties were granted joint legal and physical custody of the child in their consent divorce judgment. The child primarily resided with plaintiff. The defendant-father had parenting time on alternate weekends from Thursday to Monday morning, and two nights a week when he did not have weekend parenting time. He availed himself of almost 100 percent of his parenting time. Plaintiff and the child made the move in August 2007 to a city 400 miles away in the LP, prior to the October 2007 evidentiary hearing. Plaintiff testified at the hearing she earned $4 an hour plus tips while employed in the UP, and earned $10 an hour at her new employment. She also described her new residence, with a separate bedroom and a full connected bathroom for the child, as "better than what we were living in up there." In its written opinion denying plaintiff's motion, the trial court explained despite the higher paying job and better housing, it was not convinced the change of legal residence had the capacity to improve the child's quality of life. While the move did not appear inspired by any obvious desire by plaintiff to defeat the parenting time schedule, it frustrated defendant's ability to exercise his parenting time pursuant to the current schedule. The record showed the child had no family in the new locale other than plaintiff, but a large extended family existed in the UP community where they resided until the move. While the court might have decided plaintiff's higher wages had the capacity to elevate the quality of the child's life, it was a close question and the trial court's finding was not against the great weight of the evidence.

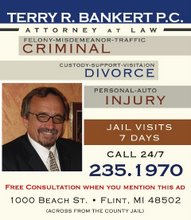

If you have questions about your rights in Family Court, divorce, custody, support or parenting time please call. If you read this article there will be no charge for the initial consultation. Call Terry Bankert 235-1970

A parent with joint legal custody who seeks to relocate more than 100 miles away must

establish by a preponderance of the evidence that a change in the minor’s domicile is warranted.

In considering a proposed change of a child’s domicile after a divorce, a

court must consider the D’Onofrio1 factors, which are codified at MCL 722.31(4), and provide

that a court must address the following:

(a) Whether the legal residence change has the capacity to improve the

quality of life for both the child and the relocating parent.

(b) The degree to which each parent has complied with, and utilized

his or her time under, a court order governing parenting time with the child, and

whether the parent’s plan to change the child’s legal residence is inspired by that

parent’s desire to defeat or frustrate the parenting time schedule.

©) The degree to which the court is satisfied that, if the court permits

the legal residence change, it is possible to order a modification of the parenting

time schedule and other arrangements governing the child’s schedule in a manner

that can provide an adequate basis for preserving and fostering the parental

relationship between the child and each parent; and whether each parent is likely

to comply with the modification.

(d) The extent to which the parent opposing the legal residence change

is motivated by a desire to secure a financial advantage with respect to a support

obligation.

(e) Domestic violence, regardless of whether the violence was directed

against or witnessed by the child.

After reviewing the record in this case, we find that the circuit court considered each

factor mandated by MCL 722.31(4).

The parties were granted joint legal and physical custody of the child in their consent divorce judgment. The child primarily resided with plaintiff. The defendant-father had parenting time on alternate weekends from Thursday to Monday morning, and two nights a week when he did not have weekend parenting time. He availed himself of almost 100 percent of his parenting time. Plaintiff and the child made the move in August 2007 to a city 400 miles away in the LP, prior to the October 2007 evidentiary hearing. Plaintiff testified at the hearing she earned $4 an hour plus tips while employed in the UP, and earned $10 an hour at her new employment. She also described her new residence, with a separate bedroom and a full connected bathroom for the child, as "better than what we were living in up there." In its written opinion denying plaintiff's motion, the trial court explained despite the higher paying job and better housing, it was not convinced the change of legal residence had the capacity to improve the child's quality of life. While the move did not appear inspired by any obvious desire by plaintiff to defeat the parenting time schedule, it frustrated defendant's ability to exercise his parenting time pursuant to the current schedule. The record showed the child had no family in the new locale other than plaintiff, but a large extended family existed in the UP community where they resided until the move. While the court might have decided plaintiff's higher wages had the capacity to elevate the quality of the child's life, it was a close question and the trial court's finding was not against the great weight of the evidence.

If you have questions about your rights in Family Court, divorce, custody, support or parenting time please call. If you read this article there will be no charge for the initial consultation. Call Terry Bankert 235-1970

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)