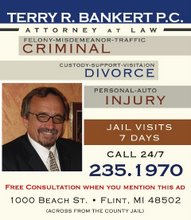

Flint Divorce Attorney article on alimony or Spousal Support. Terry Bankert is also a Flint Divorce Attorney handelings child custody and child support issues. These actions in Flint Divorce also deal with Parenting time and Grandparents rights.

This article is posted to the writing page of Flint Attorney Bankerts webpage under writings. It shall appear on his FaceBook (1200 Friends), Blogging for Michigan and his daily thread " Good Morning Flint" found on FlintTalk.com and Bankerts Google and Word press Blogs. Divorce Attorney Bankert will also discuss Alimony Payments on WFLT 1420 A.M. Radio 9 A.M. to 9:30 on 3/07/09.

Issues:

Divorce;

Motion for a reduction of alimony payments;

Motion for an increase in spousal support; Moore v. Moore; Rickner v. Frederick; MCL 552.28; Staple v. Staple;

Whether because the property settlement was not merged into the judgment of divorce the alimony was not subject to modification; Marshall v. Marshall;

Whether there was evidence the plaintiff-husband needed support to be reduced; Thornton v. Thornton; Stoltman v. Stoltman;

Retroactive modification of alimony; Staff v. Johnson; MCL 552.603(2); Rapaport v. Rapaport;

Calculation of the modified award in reliance on a "fictional rate of return"; Charbeneau v. Wayne County Gen. Hosp.

Court: Michigan Court of Appeals (Unpublished)

February 24, 2009

Oakland Circuit Court No. 280286

Case Name: Goldberg v. Goldberg

e-Journal Number: 41933

Judge(s): Per Curiam - Fort Hood, Wilder, and Borrello

This presentation is modified consult an attorney before you rely on its contents.

THE HIGHER COURT SAID THE LOWER COURT DID IT RIGHT

The trial court properly granted the plaintiff-husband's motion for a reduction of alimony payments modifying the alimony agreement where the agreement was modifiable and plaintiff proved a change in circumstances.

THE WORDS USED ARE IMPORTANT

The alimony provision in the property settlement did not specifically declare the parties were forgoing their statutory right to modification, nor did the alimony provision state it was "final, binding and nonmodifiable."

THE RIGHT TO CHANGE ALIMONY WAS NOT GIVEN UP

Further, the judgment of divorce did not address any waiver of modifiability of the alimony provision.

WIFE SAID HUSBAND DID NOT DO THE JUDGEMENT RIGHT

Defendant-wife contended the property settlement was not merged into the judgment of divorce, and thus, the alimony was not subject to modification.

A CASE CALLED MARSHALL WAS CONTROLLING

The court held Marshall did not preclude the modification of the alimony agreement in this case.

MARSHALL WAS A PROPERTY CASE

First, Marshall explicitly applies to property settlements and does not reference alimony directly.

A PRIOR AMENDMENT LET ALIMONY IN

More importantly, review of the record revealed the parties stipulated in 1987 to modify the judgment of divorce to include the alimony provision.

NOBODY WAIVED THE RIGHT TO CHANGE ALIMONY

Thus, defendant's reliance on the Marshall decision was misplaced, and it was presumed the parties did not intend to waive their statutory right to modify the alimony agreement. The parties entered into the stipulation for modification of the judgment of divorce on October 23, 1987. The stipulation demonstrated the parties intended to amend the judgment of divorce to include the alimony provision, as opposed to allowing it to remain a provision of the property settlement.

CHANGE IN CIRCUMSTANCES HUSBANDS INCOME DOWN AND WIFE INHERITIED

While the defendant also argued the trial court erred in reducing spousal support because there was no evidence plaintiff needed support to be reduced, the court disagreed. Plaintiff established his income had decreased and the defendant inherited a large sum from her mother. The court held the trial court was justified in modifying the alimony agreement. Affirmed.

– the complet case follows, above has been modified for presentation--

S T A T E O F M I C H I G A N

C O U R T O F A P P E A L S

HOWARD S. GOLDBERG,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

UNPUBLISHED

February 24, 2009

v No. 280286

Oakland Circuit Court

ALICE D. GOLDBERG,

LC No. 83-255799-DM

Defendant-Appellant.

Before: Fort Hood, P.J., and Wilder and Borrello, JJ.

PER CURIAM.

Defendant appeals by leave granted an order granting plaintiff’s motion for a reduction of

alimony payments and denying defendant’s motion for an increase in spousal support. We

affirm.

Defendant first asserts the trial court erred in modifying the alimony agreement because

the agreement was non-modifiable. We disagree. The goal of alimony is to balance the incomes

and needs of the parties in such a manner that neither party will be impoverished; rather it should

be based on what is just and reasonable under the circumstances. Moore v Moore, 242 Mich

App 652, 654; 619 NW2d 723 (2000). Upon a showing of changed circumstances, the alimony

award can be modified, but the modification must be based on new facts or changed conditions

arising since the judgment of divorce. Id. The trial court’s factual findings regarding the

modification of an alimony award are reviewed for clear error. Id. "A finding is clearly

erroneous if the appellate court is left with a definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been

made." Id. at 654-655. There is a statutory power to modify alimony that is not contingent upon

triggering language contained in the judgment. Rickner v Frederick, 459 Mich 371, 379; 590

NW2d 288 (1999).

Pursuant to MCL 552.28, individuals in Michigan have a statutory right to petition a

court for a modification to a judgment of alimony.1 "[T]he statutory right to seek modification

1 On appeal, neither party discusses the statutory right to modification of an alimony award.

However, the statutory right existed in 1983 at the time the parties agreed upon the alimony

provision. See Esslinger v Esslinger, 9 Mich App 11; 155 NW2d 702 (1967).

of alimony may be waived by the parties where they specifically forgo their statutory right to

petition the court for modification and agree that the alimony provision is final, binding, and

nonmodifiable." Staple v Staple, 241 Mich App 562, 578; 616 NW2d 219 (2000). In

continuing, the Court explained:

Without prescribing any "magic words," we hold that to be enforceable,

agreements to waive the statutory right to petition the court for modification of

alimony must clearly and unambiguously set forth that the parties (1) forgo their

statutory right to petition the court for modification and (2) agree that the alimony

provision is final, binding, and nonmodifiable. Furthermore . . . this agreement

should be reflected in the judgment of divorce entered pursuant to the parties'

settlement. [Id. at 581.]

In the present case, the alimony provision in the property settlement did not specifically

declare that the parties were forgoing their statutory right to modification, nor did the alimony

provision state that it was "final, binding and nonmodifiable." Furthermore, the judgment of

divorce did not address any waiver of modifiability of the alimony provision.

Defendant contends that the property settlement was not merged into the judgment of

divorce, and therefore, the alimony is not subject to modification. In Marshall v Marshall, 135

Mich App 702, 708; 355 NW2d 661 (1984), this Court stated, "[t]raditionally, once the parties

enter into a property settlement and obtain approval of it, the trial court may not modify the

settlement in the absence of fraud, duress or mutual mistake, or for such other causes as any

other final judgment may be modified." Because there was no evidence presented of fraud,

duress or mistake, defendant asserts the trial court did not have the authority to modify the

alimony provision that was contained in the property settlement.

We conclude that Marshall does not preclude the modification of the alimony agreement

in this case. First, Marshall explicitly applies to property settlements and does not reference

alimony directly. More importantly, review of the record reveals that the parties stipulated in

1987 to modify the judgment of divorce to include the alimony provision. Therefore,

defendant’s reliance on the Marshall decision is misplaced, and it is presumed the parties did not

intend to waive their statutory right to modify the alimony agreement.2 The parties entered into

the stipulation for modification of the judgment of divorce on October 23, 1987. That stipulation

begins as follows:

It is stipulated by and between the parties, Howard S. Goldberg, Plaintiff

and Alice D. Goldberg, Defendant, that the Judgment of Divorce of June 24, 1983

may and the same shall be amended to provide as follows:

2 The record reveals that the parties modified the alimony provision on other occasions. More

importantly, at the commencement of the underlying hearing, defense counsel agreed that

alimony was modifiable and, in fact, sought an increase in alimony. At the continuation of the

hearing, defense counsel raised the Marshall decision, despite the prior case history.

I. Alimony

Alimony shall be paid by Husband to Wife in the amount of [. . .]

This stipulation demonstrates that the parties intended to amend the judgment of divorce to

include the alimony provision, as opposed to allowing it to remain a provision of the property

settlement. Accordingly, the trial court was entitled to modify the alimony award, MCL 522.28.

Defendant next contends the trial court erred in reducing spousal support where there was

no evidence that plaintiff needed support to be reduced. We disagree. This Court reviews a trial

court’s factual findings in relation to an order modifying alimony for clear error. Thornton v

Thornton, 277 Mich App 453, 458; 746 NW2d 627 (2007). If the factual findings were not

clearly erroneous, the trial court’s ruling is reviewed to determine whether it was "fair and

equitable in light of the facts." Id. at 458-459. "This Court must affirm the trial court's decision

regarding spousal support unless we are firmly convinced that it was inequitable." Id. at 459.

In the present case, defendant improperly asserts that a modification of alimony is only

proper when the party who makes the alimony payment is capable of demonstrating that he or

she is no longer able to make the payment. To the contrary, Stoltman v Stoltman, 170 Mich App

653, 659; 429 NW2d 220 (1988), the case upon which defendant relies, stands only for the

proposition that the party who petitions the court for a change in alimony carries the burden of

proving that the circumstances justify the proposed change. Here, because plaintiff proved such

a change in circumstances by demonstrating that his income had decreased and that defendant

inherited a large sum from her mother, the trial court was justified in modifying the alimony

agreement.

Defendant next contends the trial court erred in making the modification of alimony

retroactive. We disagree. "The interpretation and application of court rules and statutes presents

a question of law that is reviewed de novo." Staff v Johnson, 242 Mich App 521, 527; 619

NW2d 57 (2000).

As provided by MCL 552.603(2), "[r]etroactive modification of a support payment due

under a support order is permissible with respect to a period during which there is pending a

petition for modification, but only from the date that notice of the petition was given to the payer

or recipient of support." In arguing retroactive modification was inappropriate, defendant asserts

that plaintiff prevented the evidentiary hearing from occurring in a timely manner and the

modification essentially would force defendant to live off of her savings for two years while

support was not being paid. In making such an argument, defendant cites to Rapaport v

Rapaport, 158 Mich App 741, 752; 405 NW2d 165 (1987), for the proposition that "the recipient

of spousal support should not have to invade her savings to support herself." Defendant is

incorrect. Rapaport explicitly states that the plaintiff in that particular case should not have to

invade her personal assets to pay attorney fees. Attorney fees are not at issue in this case.

Moreover, there is no record evidence holding that plaintiff deliberately delayed the proceedings

to create a hardship, and any delay is not relevant to the merits of plaintiff’s petition for

reduction.

Defendant further argues that because her inheritance was not received until four months

after the petition was filed, retroactive modification was improper. The trial court has discretion

to retroactively modify the alimony payment and took into consideration undue hardship as well

as defendant’s substantial assets. MCL 552.603(2). On this record, we cannot conclude that the

trial court abused its discretion.

Finally, defendant asserts the trial court erred in calculating the modified award in

reliance on a "fictional rate of return." We disagree. Review of the record reveals that plaintiff

offered testimony regarding rates of return, while defendant introduced evidence of her assets,

income, and obligations. After the trial court ruled on the reduction of alimony, defendant filed a

motion for reconsideration seeking to introduce evidence of her rate of return. The trial court

denied the motion for reconsideration. It is not an abuse of discretion to deny a motion for

reconsideration based on facts or legal theory that could have been pleaded or argued before the

trial court’s original order. Charbeneau v Wayne Co General Hosp, 158 Mich App 730, 733;

405 NW2d 151 (1987).

Affirmed.

/s/ Karen M. Fort Hood

/s/ Kurtis T. Wilder

/s/ Stephen L. Borrello

Friday, March 06, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)